Rating: Good / ★★★½

Genre: Weird Western / Horror

Series: Hexslinger, #1

Release Date: January 1, 2010

Publisher: ChiZine Publications

Content Includes: Explicit violence, explicit sex, homicide, war, execution by hanging, gore, dismemberment, dubious consent, graphic sexual assault, racism and racist slurs again Chinese, Black, and Indigenous people, homophobia and homophobic slurs, transphobia, child prostitution, terminal illness, addiction, mention of abortion, cultural appropriation

A Book of Tongues by Gemma Files is a beautifully written, moody, horrifying, culturally appropriative work that refuses to contend with the racist notions that it and its characters perpetuate because it incorporates its racism under the guise of authenticity to its historical period and of progressive criticism, but because all the elements of the book are otherwise strong, neither the characterization nor worldbuilding require the blatant injections of racism to embody the western era nor to add to the book’s ongoing discourse. So these additions stand apart as strange and unnecessary choices that eject readers, particularly readers of color, from the text, making this work safest for those that the text is supposedly criticizing: white men, a group that occupies the novel’s full attention as the main characters are queer white men who buck against societal expectations of masculinity during this period and are in complicated, messy relationships with one another. While the development of those relationships is interesting and delicious in its ambiguity, it is also troubled and like the topic of racism, there is little marking of the harm caused within these relationships.

A Book of Tongues follows Reverend Rook, a hex, and his romantic partner Chess Pargeter as they lead an outlaw gang in the Old West when Rook is called by visions of an ancient goddess. Following the goddess’ call leads Rook to make a series of world-ending decisions.

There were several engaging aspects, primarily the relationships between Asher Rook, Chess Pargeter, and Ed Morrow, the cosmic horror, and the prose in which all of the above was rendered.

Chess Pargeter is a petite redheaded gay man who favors a tailored purple suit and an ear pierced with a “woman’s bauble.” He’s the son of a prostitute and turned to prostitution himself, but is most defined by his violent predilections. He’s a man so infatuated with killing that he enlisted with the Confederacy so he could kill “bluebellies” for fun. But he comes to love Asher Rook, a Christian chaplain that, when sentenced to execution, comes into supernatural power. Escaping the noose, he leads a group of Confederate deserters westwards as newly formed outlaws. Their terror across the American west is violent as Asher learns to control his power, catching the attention of the Pinkertons. They send Edward Morrow, a straight-laced man of the law, to infiltrate Rook’s gang and bring him down.

None of these characters are likable, but they’re so far from the model gay that it’s compelling to feel for the bottom of their depravity (and to gasp in awe as we go ever deeper, without apparent end). As individuals, they’re flawed: violent, hateful, selfish. Together, their interlocked power imbalances eschews romantic notions, but hatches out the soft edges of their shadows.

In “The Gay Appeal of Toxic Love,” James Somerton eloquently argues that many queer viewers are attracted to inherently problematic fictional couples because already they empathize with the monster within stories and see within such romances similarly imperfect or harmful relationships from their own lives. “It’s like we…are so conditioned to seeing the person behind the monster that we overlook the elements that are genuinely monstrous because to us, as historical societal outcasts who lacked connection to human society at large, we value the human connection enough to tolerate or even condone monstrous behavior.” Here, Chess and Rook are devoted to their abusive relationship and to being with or near each other, they fear what each other might do and they seek out one another even when the other has horribly wronged them. Their love is not aspirational nor instructive. It’s the result of two traumatized individuals finding their likeness in another and being unable to turn away from the visage.

Ed Morrow plays a more typical role; he’s witness, allowing readers to observe the goings-on through a fresh lens that will necessarily describe events with awe, as they are all new to him, and through these observations he’s discovering his own queerness. His judgemental heteronormative stance is a method by which to distance himself from what he fears. Within Chess Pargeter’s proud profanity, his unwillingness to adhere to what others say he must be or how he must act, Ed sees something that he wants and he recognizes a part of himself which he fears. Ed’s gay awakening becomes that much more poignant with his being a lawman and his sexuality being outlawed. If something so crucial to one’s person is a crime, then why not engage and pursue the other illicit activities that society discourages?

It it through Morrow that we witness Rook and Pargeter’s tenderness towards one another, a role that culminates in his first and second instance of voyeurism. Though Pargeter is unaware that Morrow watches them having sex, Rook is — and he welcomes Morrow’s gaze, teasing him as if knowing what will ultimately occur, that Morrow will come to desire Pargeter in the same way that Rook had, that their journeys echo one another’s in their formation of sin and their self-conception as sinful for their desires.

Morrow is horrified by the feelings awakened by the outlaws and his horror is accentuated having seen the violence they enact on others and the ungodly miracles Rook is able to perform. That visceral, visual detail is writ throughout.

Horror depends upon description to deliver its genre elements, typically in the form of atmosphere and escalating tension. Even its weirder permutations, such as Algernon Blackwood’s The Willows, uses description to examine backgrounded elements and bring them to the forefront as horrific devices. Anticipatory horror is absent in A Book of Tongues, Files instead creates detailed images of deformed bodies or gore that are made stranger by their inclusion inside the mundane. Regularly, Files drops down into physical descriptions.

Revealing — a torso like an awful wax-rendering, anatomically denuded: bloodless neck, skin to her cleavage, and from thence on down nothing but a set of flapping ribcage-sides all wet red and whitish yellow, gristle-strung haphazardly together only at the bisected breastbone, the glistening spinal column. Guts coiled inside, and above that the heart, hung like a fruit — bright, hot, fluttering with life. Smoking with it.

Here, long passages grounded in grotesque physicalities seek to shock by its visceral sensation. And it does so constantly, which can quickly drain the readers energy by the sheer quantity of these dense passages. But I enjoyed the prose and felt it successfully individualized this book from those similar, but the things I liked about it were overpowered by the mishandling of race.

The book is built upon a premise that is already controversial, as it’s about two white men that are possessed by Mayan gods, and while it uses the imagery of Mayan mythology to great effect, its use of this mythology is culturally appropriative and is made no better by the use of racial epithets towards characters of color or its unexamined ideology exhibited primarily in the white protagonists.

God created men, Colonel Colt made them equal

Samuel Colt

The above is Chess Pargeter’s favorite quote. It’s a commercial ad line to sell guns, which also speaks to the heart of the issue in this book in the way that it contends with racism as the quote assumes that humanity lays with men rather than people — as in, regardless of gender — and men are created unequally, that some are naturally inferior, and that those that are inferior require weapons to become dominant. This is a message that the characters, whose power and/or positions already elevates them above the common citizen, absorb uncritically.

There are several instances within A Book of Tongues of racial epithets or racist language being used against or about Chinese people, Indigenous people, Jewish people, and Black people, but these passages could have been excised while still communicating the bigotry of the characters and their world. In fact, A Book of Tongues is quite successful in implying ideology without needing to directly use epithets or making offensive statements. It is there in their attitude: their scorn for the Chinese, their attributing “proud” to the Indigenous, or to their utter and complete ambivalence to Black struggle during the Civil War or to the stated purpose of the war to abolish slavery. Their positioning is made quite clear even in the passages in which the characters are being written to express a lack of opinion, or to appear as if pushed along by the currents of circumstance rather than having had choice in their lives and the purposes they served. This is most defined in Pargeter and Rook’s first meeting in the Confederate army.

Pinkertons’ slimy ring — a damn gang like any other, for all they had that staring sleepless eye-totem to watch over them, and drew their cheques at the same government trough as the Bluebellies.

Lines like these are more than enough to fully render the ideology of the book’s characters without also using slurs; we understand that these men are racist fucks because they repeatedly look down upon any effort for abolition. Being neutral on slavery is a big red flag as far as political ideology.

A work that chooses to use racist ideology and language is enacting a great price upon that work; for the use of these words, readers of color can reasonably expect the psychic damage of that relived trauma to be narratively acted upon in such a way that the language is justified. In other words, the work actively engages with racism and therefore uses racist language. The language is not left inert to be the racist decor on the front porch. That purpose isn’t present in A Book of Tongues. The price of the language is high and the work doesn’t afford its price, because though it draws upon racist language overtly, it doesn’t dissemble, question, or criticize racism, whiteness, or privilege.

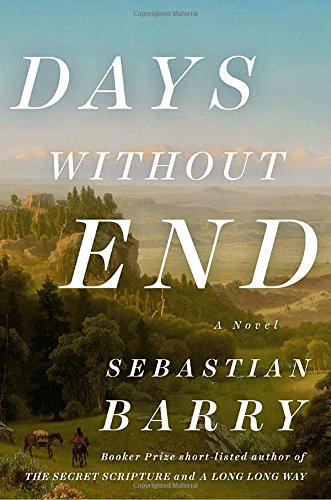

Earlier this year I read Sebastian Barry’s poignant Days Without End. It was a crucible of suffering following the lives of career soldiers, brothers-in-arms, and lovers, Thomas McNulty, an Irish immigrant who comes to identify as a woman, and John Cole, their mixed race lover and constant companion of over twenty years, during the Indian Wars and then later, the Civil War. The projects of Days Without End and A Book of Tongues are completely different but they both include queer couples at war and racism as secondary topics that are often touched upon in the most violent fashion. And though Barry’s novel is brutal, it earns that brutality. It earns the racial epithets by consuming sizable energy into examining and unpacking racial relationships in the developing west and by including multiple characters of color, albeit with varying degrees of success.

Files’ A Book of Tongues fails on both these fronts, neither earning the use of violent imagery against characters of colors nor the flippant language. A Book of Tongues treats racism as if it’s something to pepper a text whilst completely dodging the characters’ relationship to their whiteness, to racism, or even to the institution of slavery that they are protecting by willingly enrolling in the Confederate army. They are given the most vague opinions of not _really_ caring about the politics whilst also having a clear disdain for “bluebellies” or Union soldiers, abolitionists, and vaguely for President Abraham Lincoln and the equality that he means to enact through the Emancipation Proclamation. That is where their, and the book’s, examination of race stops. This deliberate vagary comes off as dishonesty about the characters’ actual position and roles in order to maintain reader closeness. They’re given the mercy of plausible deniability in their acidic bigotry but they do not deserve the space that the text creates.

The narrative centers white men and yet uses Mayan mythology and culture as its rule of cool engine. It doesn’t do so intelligently nor does it use that material to make a broader comment. All figures coming from Mayan mythology are depicted as dark, evil, and monstrous. The basis of the plot is that bringing Mayan gods back into the world will throw it into apocalypse.

So that was the world she wanted to bring about again, in a nutshell — the Mayan-Aztec Death Factory, a cotton gin of severed heads and heart-smoke, built on whitewashed bones. And he was going to help her do it, he supposed. Not so much in order to get what he wanted as … not lose what he had.

PG 164

It’s necessary to examine how the text handles this aspect over time before saying if it successfully used the material, but as it stands, the way Mayan mythology is grafted on is often appropriative for the sake of adding an exotic threat.

Each instance of racism within A Book of Tongues is a deliberate choice of the author’s. Citing historical accuracy obscures their agency in crafting this work for consumption and attempts to remove their work from the purview of criticism, but the racist language and ideology cannot be set aside. They’re part of the same imaginative cruft as the characters and world, as they are not history. They are an imagined view of history. Here, dramatically reduced and contorted to fit within the narrative and serve a particular function, one of an authenticity that posits racism is essential to the narrative of the American West, no matter how divorced the fictive setting is in every other historical context.

Clearly, I had many issues with the text, but I kept reading because I’m used to compartmentalizing hurtful narratives in order to take joy in the aspects that I do love and the genre fusion between weird fiction, westerns, and queer horror amalgamate my childhood nostalgia for black and white westerns with my current literary bend; so, I just like this sort of thing, and I plan to continue in the series.

Those that might also like this series are regular readers of weird fiction and cosmic horror who would enjoy seeing these genres inhabited by murder gays, and who are also capable of finding joy in works that don’t love you back.

Leave a Reply